Cachar

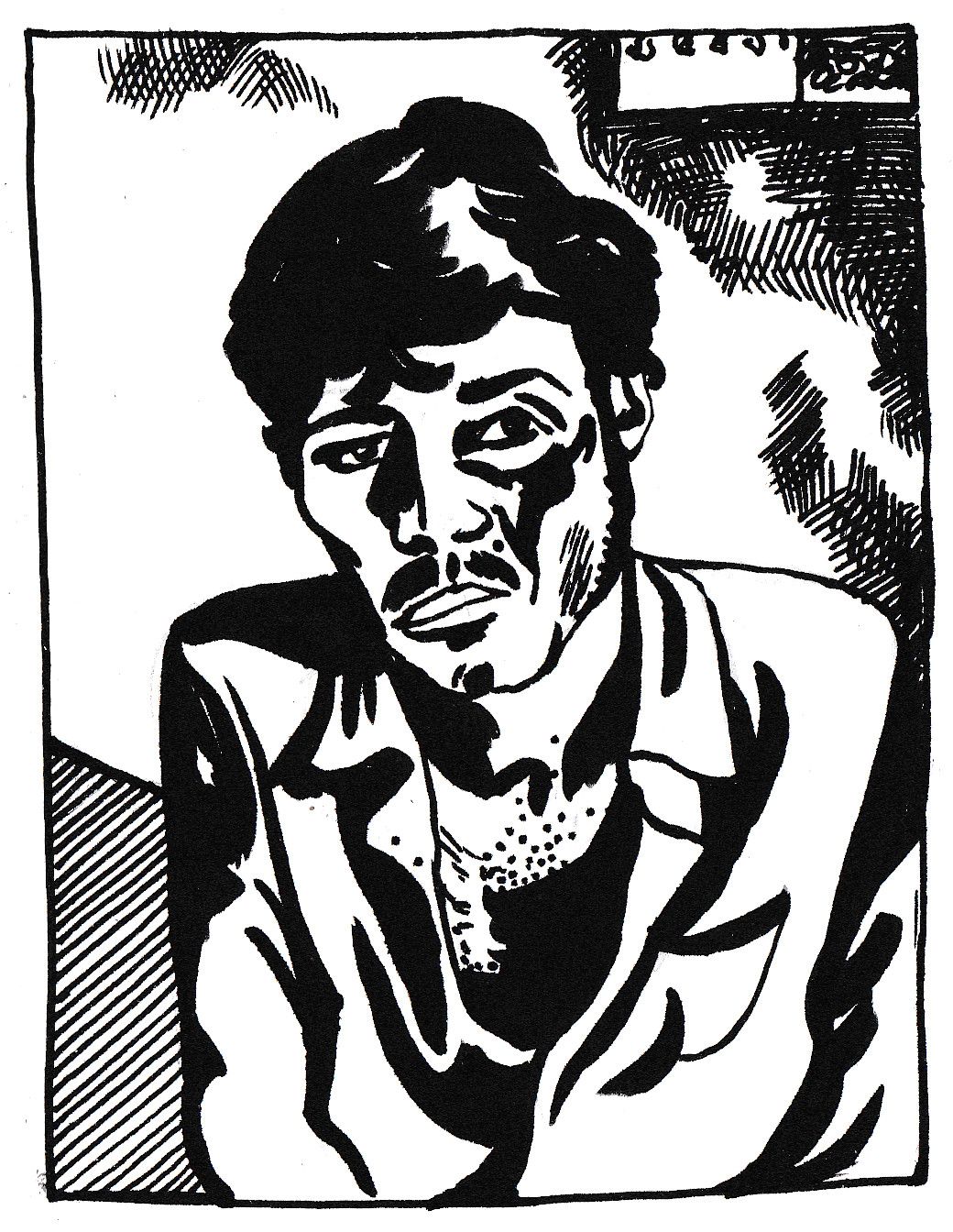

Testimony OfMinara Begum

Minara Begum is nearly 47-years-old. She cannot read or write and failed to comprehend her lawyer's instructions for her NRC documents. And so, despite her father's name on the 1965 voters' list, she was declared a foreigner in 2011 and taken to a detention camp. Her daughter, Sahana, barely two-weeks-old, grew up inside the detention camp.

Eleven years later, when Minara Begum was released, she discovered that three of her four daughters had been married off and her husband had another wife. She now lives with Sahana in a house made of bamboo and tin sheets. When we visited her, a broken Minira asked us, “Who will give me back my children's childhood years that I missed?”

Eleven years ago, just days after she had delivered her baby, Minara Begum had put her little daughter to bed and sat to boil water for herself. It was seven in the evening. With no warning, a policewoman barged into her kitchen and grabbed her by her arm. Two more policemen came in. “Are you Minara?”, they asked. She was too stunned to reply. She was asked to fetch her documents; they were taking her to the police station.

Minara Begum was first taken to Udarbond Police Station. She had no idea why she had been picked up. That night she was given a bed but no food. She had her newborn baby with her. Her husband who had followed her to the police station brought her something to eat. The next day at 10 a.m., she was taken to the office of the Superintendent of Police (Border). They took her photograph and fingerprints and sent her to Sadar Police Station, Silchar where she spent the next night. This time she was only given a filthy blanket to sleep on.

The next day at 6 p.m., Minara Begum was made to board a train. She was accompanied by two women police officers and three policemen. She was the only person they were taking. There was no physical abuse, but she had no idea what was going on or where they were taking her. There was no official communication to her or her family. One of the lady officers was helpful and gave her personal number to Minara Begum's husband. She let him know that they were headed to Goalpara but nothing more. The journey took 22 hours and on the way, the little baby got a fever.

Goalpara was a newly-built detention centre. Upon her arrival, Minara was given a mosquito net and a blanket. There was no food – she had arrived after the meal-time. Her husband had given her a bottle of water and a packet of biscuits so she ate those and went to sleep. The room was small and had 19 other women. Everyone slept on the floor. There were six such rooms for women. Two women police officers would guard them in the morning and two at night.

Every evening after dinner, which was served at 4 p.m., the women were locked in their rooms. In the winters, dinner was served at 3.30. When the doors were unlocked at 5 in the morning, they would spend the day in the open space outside.

At the camp, there was no facility to speak to her family. Sometimes she would borrow the police officer's phone and give a missed call to her family and they would call back.

Minara Begum's husband came to visit her in 2012. For a family that barely managed to get by, this was not something they could afford often. He never visited her again.

When Minara's daughter, Sahana turned four, she began going to school at the detention camp. Meanwhile, a police officer told her that other detainees were able to get bail and go home. Her family had no idea how to go about this.

It took three long years before Minara Begum was released. She was ordered to report to the police station every Wednesday and register her thumbprints. Each visit costs her 40 rupees – even that was too much for her. Minara’s biggest worry now is her 11-year-old daughter, Sahana, and how she will raise her with no means or support.